Many of the leading causes of illness and death in the U.S. are multidimensional, generated by a complex interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors (Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). It is thus becoming clear that the challenges facing our health care system cannot be solved using uni-disciplinary, cross-disciplinary, or multi-disciplinary approaches (Holley, 2009; Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). In 2000, the Committee on Building Bridges in the Brain, Behavioral, and Clinical Sciences identified neuroscience as a prime example of an interdisciplinary field which can significantly contribute to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of human diseases (Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). To study the neural elements underlying human behavior, neuroscientists combine the strengths and practices inherent to medicine, psychiatry, psychology, biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, engineering, mathematics, linguistics, and philosophy (Basu et al., 2017; Crisp & Muir, 2012; Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). Synthesizing and extending discipline-specific theories to create novel methodologies that are relevant to all involved disciplines (Modo & Kinchin, 2011), neuroscience is a striking counterexample to the misconception that science is a collection of isolated disciplines (Ramirez, 1997).

In academia, the field of neuroscience is flourishing. In the last few decades, a dramatic increase in the interest of undergraduate students in neuroscience education has been documented, paralleled with an tremendous growth in the number of newly created neuroscience programs. While only seven U.S. institutions offered a neuroscience major in 1986, this number increased to 221 institutions by the 2017–2018 academic year, and over 7000 students had graduated that year with majors in neuroscience (Ramirez, 2020; Rochon et al., 2019). When interdisciplinary neuroscience education is intentionally integrated into the academic curricula, it has the potential to demonstrate the interconnectedness of the sciences and bridge the gap between the sciences and the humanities (Ramirez, 1997; Ramirez, 2020). It complements students’ scholarship with the ability to assimilate complex ideas into a cohesive knowledge structure, enhance their philosophical inquiries (e.g., the nature of consciousness), and strengthen their ethical awareness (Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Ramirez, 1997). It also prepares students for entrance into graduate and professional school (Ramiraz, 1997), allow them to acquire competencies suitable for a variety of careers that reach well beyond research and medicine (Phillips & Sontheimer, 2023), and support their development into an adaptable, knowledgeable, and skilled workforce (Modo & Kinchin, 2011).

Importantly, investment in college-based neuroscience education is also seen in small colleges and universities. These schools, which often lack the resources to start new majors, respond to the demand by developing neuroscience-focused minors, which augment their undergraduates’ chosen majors with neuroscientific knowledge (Flaisher-Grinberg, 2022; Franssen et al., 2022). These interdisciplinary minors are not housed in a single school, nor are they identified with a single department. Rather, they bring together faculty from disparate departments (biology, psychology, chemistry, engineering, communication sciences, kinesiology, physical therapy, occupational therapy, management, economics, etc.), who combine resources, viewpoints, and expertise into a continuous and holistic curriculum (Crisp & Muir, 2012; Franssen et al., 2022; Latimer et al., 2018; Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Phillips & Sontheimer, 2023).

Despite the progress in neuroscience education seen in the last few decades in higher education, public access to such knowledge is limited. Even though the public is fascinated with neuroscience (Gage, 2019; Phillips & Sontheimer, 2023; Sperduti et al., 2012) and can easily recognize its relevance to daily lives experiences (Franssen et al., 2022; Myslinski, 2022), neuroscience literacy in the general public remains poor (Haynes & Jakobi, 2021; Herculano-Houzel, 2002; Sperduti et al., 2012). The absence of neuroscience education in the K-12 curriculum (Davidesco et al., 2021; Franssen et al., 2022; Gage, 2019) is particularly noticeable at the high school level, where investment in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) is significant (Myslinski, 2022).

Given that K-12 neuroscience education may be hindered by the lack of adequate space, dedicated funds, accessible materials, and complementary resources (Davidesco et al., 2021; Karikari, 2015; MacNabb et al., 2006; Schleisman et al., 2018), the neuroscientific community has been charged with the creation of educational programs which will increase public awareness and comprehension of the field (Benneker et al., 2023; Haynes & Jakobi, 2021; Herculano-Houzel, 2002; Myslinski, 2022). In response, a variety of neuroscience-centered educational outreach platforms were generated, spearheaded by the Dana Foundation’s Brain Awareness Week campaign (Dana Foundation, n.d.) and the Society for Neuroscience’s Public Education Programs (Society for Neuroscience, n.d.). Such initiatives include workshops (Colón-Rodríguez et al., 2019), class visitations (Fitzakerley et al., 2013), presentations (Deal et al., 2014; Romero-Calderón et al., 2012), and small-scale festivals (Flaisher-Grinberg & Ramsey, 2019). Virtual opportunities have also been generated, including neuroscience-focused websites (e.g., Neuroscience for Kids, see review in Chudler & Bergsman, 2014), mobile applications (Schleisman et al., 2018), and computer games (Schotland & Littman, 2012). While some of these educational strategies are designed for the entire K-12 spectrum (Deal et al., 2014; Flaisher-Grinberg & Ramsey, 2019; Romero-Calderón et al., 2012), several programs are age-specific, targeting pre-K (Brown et al., 2019; Schotland & Littman, 2012), elementary (Bazzett et al., 2018; Fitzakerley et al., 2013; Fitzakerley & Westra, 2008; Toledo et al., 2020), or high-school (Colón-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Davidesco et al., 2021; Lichtenberg et al., 2020) students. Other educational avenues focus on parents (Benneker et al., 2023), teachers within the educational system (MacNabb et al., 2006), etc.

In recent years, Saint Francis University (SFU), a private catholic liberal arts college located in a rural region of Pennsylvania, has joined the effort to improve college-level and public access to neuroscience education. In 2004, SFU established an interdisciplinary neuroscience minor, built as a collaborative effort of faculty representing the biology, chemistry, psychology, physical therapy, and exercise physiology departments. In 2015, SFU faculty created a network of academia-community partnerships, through which neuroscience-focused education is provided to K-12 students in the region. Working in collaboration with staff and volunteers at local libraries, children’s museums, elementary/high schools, and scout troops, a multitude of events (including classroom visitations, interactive lectures, hands-on demonstrations, and small-scale festivals) have been regularly held on campus and within the community (Flaisher-Grinberg, 2022; Flaisher-Grinberg & Ramsey, 2019).

In 2018, this effort was expanded into a five-day neuroscience-focused summer academy for local high school students. Cohesively integrating physiological, psychological, social, and philosophical curricular components, the academy was designed as an introduction to the interdisciplinary fundamentals of neuroscience. Including a residential experience, the academy was constructed to allow participants to experience the full range of college life. We hypothesized that the academy would enhance participants’: 1) comprehension of neuroscientific themes; 2) appreciation of neuroscience as a discipline; 3) interest in college-based neuroscience education and/or the development of a neuroscience-integrated career. We also hoped that the participants would enjoy the different aspects of the academy and value the experience as a whole.

Design and Assessment

Participants

Thus far, the academy has been offered in the summers of 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2022, enrolling a total of 52 high school students (41 self-identified as females and 11 as males). All participants were 15-18 years old who live within 3 hours driving distance from SFU.

Academy Set Up

The academy was generated as a collaboration between various academic units, and as a partnership between the university and the local community. First, the author (one of the co-coordinators of SFU’s interdisciplinary neuroscience minor) worked alongside the institution’s Science Outreach Center to model the academy after some of the academies created in past years (Pre-Medicine, Chemistry, etc.). Accordingly, the academy was constructed as a 5-day residential experience, allowing enrolled high school students to experience the full range of college life. Collaboratively, we identified dorm rooms approved for high school students, coordinated a meal plan with SFU’s dining services, and bought snacks to serve in between meals. To craft an interdisciplinary program, we chose to offer faculty-delivered lectures which cohesively integrated various domains of neuroscience and to complement them with professional talks provided by invited guests, hands-on laboratory sessions, and participant-generated presentations (focusing on their chosen topic). To assist the faculty in supervising the academy, we recruited two SFU students to serve as academy mentors. The mentors organized recreational activities which took place in the evenings, and helped participants navigate campus and complete homework. To sponsor the academy (e.g., faculty and mentors’ salary, dorm rooms and meal plans, snacks), a budget was created. The Institution took responsibility for most of it, granting us the opportunity to set enrollment fees at $500 per participant (with an opportunity to request financial assistance). To advertise the academy to the public, we collaborated with local high schools, making personal connections with teachers, counselors, and principals. We also conveyed information about the academy through social media, community-based advertisement (e.g., local libraries), and conversations with current/former SFU students, employees, and their social networks. To enroll in the academy, applicants were asked to submit a short essay explaining their interest in the academy, a letter of recommendation from a teacher/counselor, a grade report, and a deposit of $30. Upon the review of the applications, participants were notified of their acceptance to the academy, and necessary information was provided (academy schedule and syllabus).

Academy Curriculum

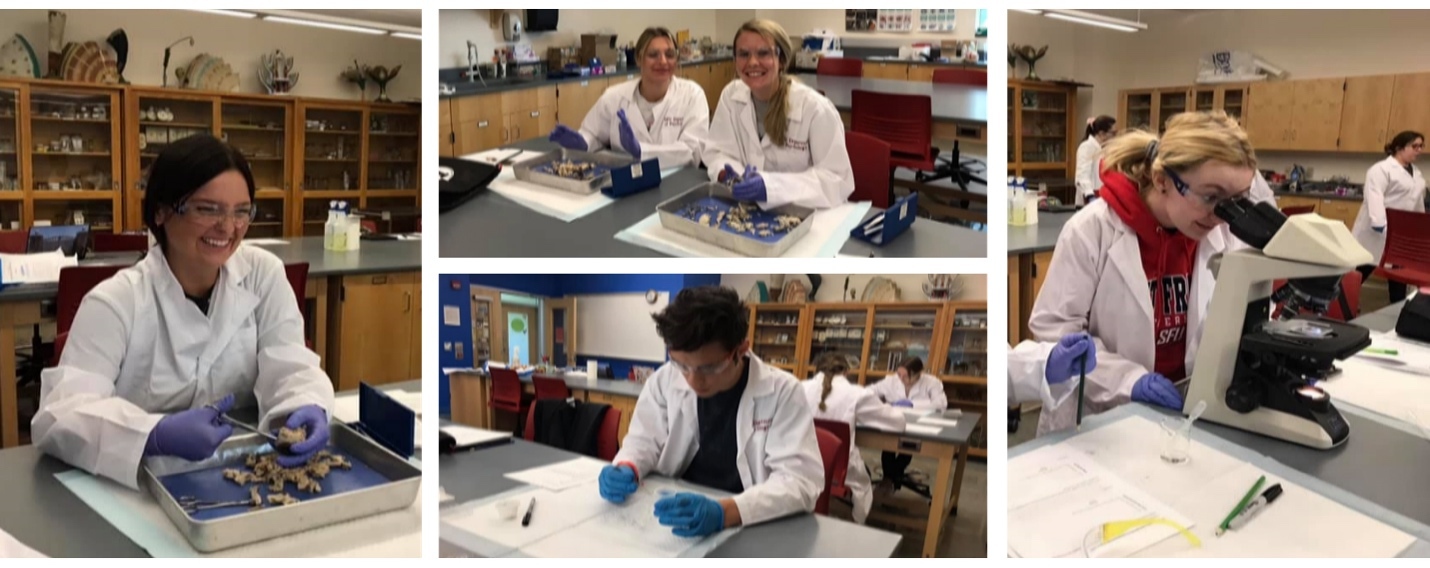

Each day of the academy was dedicated to a different aspect of neuroscience (see Table 1). Day 1, which introduced participants to the bidirectional link between physiology and behavior, explored structures of the brain which are involved in functions such as language, sleep/dreaming, decision making, personality and consciousness. Wet laboratories offered participants the opportunity to complement the topic via the dissection of sheep brains (Figure 1) and the examination of preserved rodent brains which were histologically stained for microscope-enhanced exploration. Day 2 expanded the connections among biology, chemistry, physiology, and psychology, via the investigation of the structures of the nervous system which shape our conception of the world we live in. Participants were surprised to learn that the way that we sense our surroundings is only a small part of the way that we perceive it. From a philosophical standpoint, concepts such as color or flavor are not absolute, since processes of interpretation, speculation, and estimation affect the way we see, hear, smell, taste, and touch our surroundings (Wolfe et al., 2020). Using various perceptual illusions, the dissection of a cow’s eye (Figure 1), and the creation of individual taste, smell, and touch maps, participants learned to appreciate the diverse fashion through which each of us perceive our “reality,” and the neuroscientific intersection between the sciences and humanities was further exemplified. Day 3, which was dedicated to neuropsychopharmacology, explored the effects of various drugs on human behavior. Experimenting with drug extraction (e.g., aspirin from the willow bark) and drug administration (alcohol applied to water fleas, Figure 1), the participants acquired socially relevant, drug-related knowledge (e.g., drug abuse and addiction). Via the consumption of poppy-seed muffins and the consequent detection of opioid metabolites in their saliva (Flaisher-Grinberg, 2023), they explored the social consequences of drug development, testing, policy, and enforcement. Days 4 and 5 explored the events that shape behavior, focusing on the neurological changes that take place when new skills are learned. This application of neuroscience to education, therapy and rehabilitation was complemented by the training of rats (Day 4) and dogs (Day 5), demonstrating the use of behavioral modification techniques to various species (Figure 2). In addition, the work with animals elaborated on topics of neuroethics (e.g., animal experimentation), on themes of comparative neuroscience (exploring neurological similarities and differences between humans and animals), and on the benefits of the mutual bond between humans and animals. At the end of each day, participants chose their own topics, individually studied them, and prepared presentations delivered to their classmates at the beginning of the following day.

Academy Delivery

On the afternoon prior to the beginning of the academy, participants checked in at SFU, received access to their dorm rooms, were assigned temporary laptops, and met with their instructors, mentors, and classmates. During the academy, instructional sessions were held from 9:00am-noon and from 1:00pm-4:00pm every day, with lunch at noon, dinner at 4:30pm, homework and afternoon activities from 5:00-8:00pm. The last day of the academy ended at 2:00pm and included a farewell reception (Figure 3). During the reception, participants received an Academy Completion Certificate and delivered a presentation in which they shared their work throughout the academy with their families (Figure 3). Importantly, the successful completion of the academy granted the participants 2-college credits (transferable to any college) and a $1,000/year tuition reduction (specific to SFU).

Assessments and Data Analysis

During the summers of 2018-2019, the participants’ informal feedback, the academy completion rate, and participants’ transition ratio into neuroscience-related programs at SFU/other universities were all collected (expressed as a simple percentage). During the summers of 2021-2022, a direct and formal assessment of the program was added. To evaluate the participants’ comprehension of neuroscientific themes, a knowledge quiz comprised of twenty questions was delivered on the first and last day of the academy, and scores were compared using a paired t-test analysis. Examples of questions (all multiple-choice) included: “The brain is comprised of ____ hemispheres and ____ lobes”; “A ____ is a measure of the safety of a drug”; “The tendency for an operant response to be emitted in the presence of a new stimulus that is similar to the original stimulus is known as ____” (answers: two, four; therapeutic index; generalization). To estimate the participants’ appreciation of neuroscience as a discipline, as well as interest in college-based neuroscience education/the development of a neuroscience-integrated career, an attitudes survey was delivered on the first and last days of the academy, and scores were compared using a paired t-test analysis. The survey was comprised of the following questions: 1) “I think that I understand the field of neuroscience”; 2) “the field of neuroscience has the potential to positively influence people’s lives”; 3) “the field of neuroscience has the potential to positively influence our society”; 4) “I wish that more people knew about the field of neuroscience”; 5) “I will choose neuroscience as a major or a minor when I attend college”; 6) “I will choose a career related to neuroscience when I graduate from college”. The survey was structured using the following 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree. To appraise the participants’ level of enjoyment related to the academy, a satisfaction survey was delivered on the last day of the academy, and scores were expressed as means and standard deviation across all participants. The survey solicited open-ended qualitative feedback (“please share your academy experience with us”), as well as the following quantitative closed-ended questions (using the same Likert scale described above): “In this academy, I enjoyed the” 1) “hands-on laboratories”; 2) “lectures”; 3) “activities”; 4) “discussions”; 5) “interactions with the instructors”; 6) “interactions with the mentors”; 7) “interactions with my classmates”; and 8) “I will recommend this academy to others”. Data collection was approved by SFU’s Institutional Review Board (PRO2021-026SFU). The training of rats and dogs by participants was approved by SFU’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (PRO00003 and PRO000017, respectively).

Results

All 52 participants enrolled in the academy across the summers of 2018-2019 and 2021-2022 successfully completed it (100% completion rate). Forty-two participants (80%) transitioned into neuroscience-related major/minor programs, and twenty (38.5% of total participants), transitioned into SFU.

The twenty-questions knowledge quiz scores calculated in 2021-2022 (n = 22) yielded that participants’ comprehension of neuroscientific themes improved between the first and last day of the academy [Day 1, M = 8.27 (SD = 2.07); Day 5, M = 16.05 (SD = 2.21); t(21)=12.74, p<0.0001]. The attitudes survey demonstrated that in comparison to Day 1, on Day 5 of the academy participants had higher appreciation of neuroscience as a discipline, and their interest in college-based neuroscience education and/or the development of a neuroscience-integrated career was enhanced. Specifically, in comparison to Day 1 of the academy, on Day 5 participants felt that they better understood the field of neuroscience [Day 1, M = 2.77 (SD = 0.92); Day 5, M = 3.91 (SD = 0.86); t(21)=5.38, p<0.0001], and wished that more people knew about the field of neuroscience [Day 1, M = 4.27 (SD = 0.82); Day 5, M = 4.72 (SD = 0.45); t(21)=2.21, p<0.05]. On Day 5, the participants were also more likely to indicate that they plan to choose neuroscience as a major or a minor when in college [Day 1, M = 3.13 (SD = 0.83); Day 5, M = 3.59 (SD = 0.85); t(21)=2.34, p<0.05], and that they plan to choose a career related to neuroscience when they graduate from college [Day 1, M = 2.95 (SD = 0.84); Day 5, M = 3.59 (SD = 0.85); t(21)=3.31, p<0.01]. In contrast, participants’ beliefs that the field of neuroscience has the potential to positively influence people’s lives [Day 1, M = 4.77 (SD = 0.42); Day 5, M = 4.86 (SD = 0.35); t(21)=0.42, NS], as well as our society [Day 1, M = 4.77 (SD = 0.43); Day 5, M = 4.82 (SD = 0.39); t(21)=0.74, NS], remained constant.

Both the qualitative and quantitative sections of the satisfaction survey demonstrated that across both years, participants enjoyed the academy. As can be seen in Table 2, participants’ ratings of all items scored above 4 on the Likert scale. Moreover, the qualitative feedback supported the quantitative data. Specifically, participants commented: “I feel as though I learned a lot during this academy, and I am sad that it is over. The week went by very fast, but it was an incredibly enjoyable week” (2021); “I had an amazing time here and I will do my best to carry on what I have learned. Thank you to all those who made this possible and I am thankful that I got to come here” (2021); “Amazing. Definitely do more things and events like this and I will advertise it at my school and try to get more students from my [hometown] to come here, get young minds involved, think for themselves, and question their environment and reality” (2021); “I really enjoyed this week and learned so much about neuroscience” (2021); “I’m grateful for this experience I had here and glad I came” (2022); “The academy is super useful helping make future decisions about college” (2022); “I have learned so many things this week, but enjoying it was the biggest part of all of it” (2022); “I believe that this academy has helped my interest and my education” (2022); “One amazing thing about the academy is the dedication of the professors and mentors. Everyone was hardworking and focused on the materials. The staff were helpful in any way possible, and I believe it greatly enhanced the experience of the academy” (2022); “You made us feel at home, and in turn we found a home in each other. Thank you for everything” (2022).

Discussion

The current project, which aimed to improve public access to neuroscience education via the creation of a high school student-focused summer academy, demonstrated that the initiative was successful in reaching its goals. The academy’s participants demonstrated improved comprehension of neuroscientific topics (such as neuroanatomy, neuroeducation, neuroethics, and neuropharmacology), enhanced appreciation of the field, and interest in its integration into their future. Importantly, they also enjoyed the academy and felt grateful for the opportunity to participate in it. These findings are in line with research showing that public-oriented educational endeavors positively impact the audience’s neuroscience knowledge (Brown et al., 2019; Colón-Rodríguez et al., 2019; Fitzakerley et al., 2013; Lichtenberg et al., 2020; Schleisman et al., 2018; Schotland & Littman, 2012; Toledo et al., 2020), interest in neuroscience (MacNabb et al., 2006; Schotland & Littman, 2012), enthusiasm for neuroscience (Colón-Rodríguez et al., 2019), confidence in science ability (Deal et al., 2014; Fitzakerley et al., 2013; MacNabb et al., 2006), and even the desire to attend school (Toledo et al., 2020).

The fact that academy participants demonstrated enhanced comprehension of neuroscience (demonstrated via the knowledge quiz) and felt that they better understand the field (attested via the survey) is encouraging. Public understanding of fundamental neuroscience concepts can facilitate the appropriate application of scientific advancements towards crucial societal issues by allowing the public to participate in national discourse as informed citizens capable of making intelligent decisions that affect their personal lives, as well as their nation’s economic, ethical, and scientific foundations (Haynes & Jakobi, 2021; Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Ramirez, 1997; Ramirez, 2020). Examples include policy and legislation practices related to pain management, marijuana legalization and the opioid epidemic (Uhl et al., 2019), prevention of sport-induced traumatic brain injuries (Kroshus et al., 2023), avoidance of perinatal drug abuse (Raffaeli et al., 2023), employment of neuroscience-guided education practices (Smith & Seitz, 2019), and utilization of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (Belouin & Henningfield, 2018). Enhanced neuroscientific literacy can also support public comprehension of the multifaceted factors that contribute to a variety of conditions and empower individuals to make better health decisions for themselves and their loved ones (Haynes & Jakobi, 2021; Myslinsky, 2022). Examples include aggression and violence (Blair & Lee, 2013), prejudice and discrimination (Amodio & Cikara, 2021), psychiatric disorders (Fricchione, 2018), and neurodevelopmental/neurodegenerative disorders (Michalski & Wen, 2023). Notably, the creation of public-oriented educational programs can offer neuroscientists the opportunity to dispel harmful myths and misinformation about neuroscience, increase scientific transparency, and decrease mistrust in science (Haynes & Jakobi, 2021; Illes et al., 2010; Myslinski, 2022; Smith & Seitz, 2019).

The finding that at the end of the academy participants indicated an increased interest in the integration of neuroscience into their future education and/or occupation is reassuring. Both prevailing and newly emerging health problems (such as HIV infection, heart disease, and drug abuse) are caused by an intricate interplay between the environment, behavior, and disease (Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). Thus, the next generation of scientists and health care providers must be prepared to address the burden of illness by understanding the biology of a disorder as well as the cultural and psychosocial aspects of living with it (Pellmar & Eisenberg, 2020). Interdisciplinary neuroscience education, which breaches the walls separating various scientific disciplines and overcomes the differences between the sciences and the humanities (Ramirez, 1997), can support the development of scientifically literate and technologically sophisticated individuals, who can contribute substantively to the workforce (Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Ramirez, 1997; Ramirez, 2020). The fact that at the end of the academy participants were more likely to indicate that they plan to integrate neuroscience into their future education/occupation suggests that exposure to neuroscience education during high school has the potential to affect participants’ career choices and professional trajectories. The findings showing that when academy participants enrolled into college a significant number chose neuroscience-related programs suggest that this affinity towards neuroscience translated into decisions and actions.

The findings regarding participants’ appreciation of neuroscience as a field are worthy of further discussion. At the end of the academy, participants were more likely to declare that they wished that more people knew about the field of neuroscience, but their beliefs that the field of neuroscience has the potential to positively influence people’s lives/our society remained unchanged. Although it is possible that the academy failed to fully address the social relevance of neuroscience to the lives of the participants and of people around them, an alternative explanation is possible. Specifically, on Day 1 of the academy, participants’ scores on both items were very high (M = 4.77), leaving little room for improvement on Day 5. This possible ceiling effect suggests that the participants’ positive attitudes regarding neuroscience may have existed prior to the academy and may have even been a factor contributing to their decision to pursue academy enrollment. This possibility will be explored in future academy iterations.

The fact that participants deepened their understanding of neuroscience, displayed improved attitudes towards neuroscience, and enjoyed the academy (indicated by both quantitative and qualitative assessments), may be attributed to various factors. One option may relate to the academy’s design. Contrary to the common perception that neuroscience is limited to the study of biological, anatomical, and functional aspects of the human brain (Sperduti et al., 2012), the field has the capability to elucidate a variety of complex ethical, sociocultural, political, economic, philosophical, and psychological questions (Modo & Kinchin, 2011; Phillips & Sontheimer, 2023; Ramirez, 1997; Ramirez, 2020). To exemplify the interdisciplinary nature of neuroscience, the academy introduced the participants to different facets of neuroscience (e.g., social, cognitive, comparative neuroscience), with different experts in the field (e.g., scientists and animal trainers), and with an assembly of learning activities (laboratory sessions, discussions, lectures, participants’-delivered presentations). The fact that, unlike shorter encounters with neuroscience education [e.g., a one-hour session (Fitzakerley et al., 2013), a set of 60-90 minutes lessons (Deal et al., 2014), or a one-day workshop (Colón-Rodríguez et al., 2019)], this holistic approach to neuroscience lasted 5 days may help explain its multilevel, impactful outcomes. A second possibility may be attributed to the academy’s residential nature, structured to approximate a real-life college experience. During the academy, participants slept at the university’s residential halls, ate in its dining center, and completed full days of college lectures and laboratory sessions, followed by homework assignments and recreational activities. This design may have complemented the participants’ scholarly journey with social and cultural content, creating a unique and comprehensive event.

Importantly, a few limitations to the academy can be recognized. First, the delivery of the academy required specific resources, supplies, and funds. These included classrooms, dorm rooms, meal plans and instructional resources (e.g., sheep brains and cow eyes). It also required financial compensation to instructors, mentors, and administrative staff. It is thus recommended that appropriate allocations be secured prior to the offering of such educational experiences. Second, much time and effort were invested in the promotion of the academy to local high school students. From an organizational standpoint, this task was facilitated by close collaborations with the local community allowing us to directly communicate with teachers, counselors, and school principals and to advertise the academy via community-based channels such as local libraries. It is accordingly suggested that to improve the public’s neuroscience literacy, strong academia-community partnerships must be formed. Third, despite its 5-day duration and interdisciplinary structure, some aspects of neuroscience were not thoroughly integrated into the academy. These included molecular neuroscience (Lein et al., 2017), neurorobotics (Wudarczyk et al., 2021), and computational neuroscience (Nayak et al., 2018). Although these domains were absent from the academy due to lack of instructors’ experience in these fields and access to lessons/resources, it is recommended that future educational outreach programs cover these exciting and challenging topics. Fourth, although the assessment of the academy’s impact included the ratio of students that transitioned into neuroscience-related major/minor programs, no data related to their career choices is yet available. It is advised that a longitudinal assessment of participants’ occupational trajectories be monitored in future years.

In summary, the interdisciplinary academy described above has yielded a positive impact on high-school students, enhancing neuroscience familiarity, comprehension, and interest. In the future, we hope to offer the academy more frequently (reaching a higher number of participants), add additional domains of neuroscience to its scope (extending the academy’s interdisciplinary focus), and improve the qualitative and quantitative assessment of the program. It is our hope that this initiative inspires additional scientists, educators, and their institutions to create neuroscience-based educational avenues that reach beyond academia and into local communities.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this project was provided by SFU’s “Excellence in Education” and “Faculty Development” grants to the author. We would like to thank Dr. Lanika Ruzhitskaya, Dr. Rachel Wagner, and Ms. Beth Warner for their help coordinating the academy, as well as the following academy mentors for their dedicated service: Ms. Kelly Kramer and Mr. James McCulley (2018-2019), Ms. Megan Wood (2021-2022), Ms. Hannah Primm (2021), Mr. Ty Mallin (2022). All students pictured granted permission for their images to be used in this essay.

__2022_students_sharing_their_work_with_their_familie.jpg)

__2022_students_sharing_their_work_with_their_familie.jpg)